This is a summary of a theory that I have been working on since my undergraduate days, studying Relevance Theory at UCL under its co-originator Deirdre Wilson.

It’s undercooked, but I’m pulling it out of the oven anyway. It does presume some knowledge of / interest in semantics and pragmatics, but most terms are explained eventually.

The theory tries to explain the way that children’s cognitive abilities develop. It tracks their mode of linguistic processing, social processing, semantic development and concept integration over the first decade. It provides an account of the two big evolutions that we see in these areas (at 18-24 months and at 7-8 years), explaining these as dimension shifts in the way children approach representations.

We won’t be taking a chronological approach, but we will start at the beginning.

Setting the stage

Children in the sensorimotor stage, which begins at birth, spend much of their time following their own sensory, emotional and informational drives. They connect with the adults around them, but predominantly in the course of stereotyped passages of interaction which are low in conceptual weight but high in emotional co-engagement. By spending time co-regulating in this manner, the infant is growing and enriching their concept of OTHER PERSON (hereafter OP). They are also becoming more aware of themselves as a thinking, acting entity.

Socially-related data is pouring in, among other types of data, and the infant brain is trying to make sense of it, creating corresponding systems of understanding and action. Some of this data is enabling an understanding of facial expressions, eye gaze and so on, with these being correlated with emotions, intentions and actions.

This is the emergence of ‘mindreading’: making informed guesses about someone else’s mental environment, and then knowingly attributing it to them.

Words start out as just things that happen alongside the objects and actions that make up the child’s experience. The phonological representation and aspects of the motor representation of words must, at least initially, be located inside OP, since word-related sensory stimuli originate from that source. There would more than likely be a semantic aspect, as well as a phonological aspect, to the way these representations are indexed within this concept, since the brain can’t help systematising things.

All the while, the child is building, in parallel, their own representation of their world, which exists outside of OP, and which is, at this stage, informationally encapsulated from OP.

In this age of horizontal representation, the way that words work – to summon certain favoured experiences for example – feels like magic to the child, since these lexical items are being activated within a module-like concept that doesn’t solidly register in their consciousness.

Although the words are activating simultaneously with the semantic avenues in the child’s thinking that they conventionally indicate, on a computational level, the child has no real sense that the two representations refer to the same ‘event’.

Our role in all of this is to help the child grow big, competent subconcepts of OP like MUM and GRANDDAD as we interact with them, and to start to draw more meaning into these interactions, enriching their social sense. We also need to maximise engagement, understanding and co-regulation during activities like bedtime and meal times, so that we can help the child build workable schemata (systems of understanding relating to core experiences), in pairs, as follows:

- In OP – a system encompassing and representing the words, feelings, intentions and actions of other people

- In the wider semantic system – a system encompassing and representing the child’s ideas, and their understanding and use of objects.

Shift #1: The explosion in language and learning at 18-24 months

At 18-24 months (the beginning of Piaget’s preoperational stage) the two systems become similar enough that they can operate as one in some regards. Their OP is sophisticated enough that they are now running a live scratchpad of second order representations, having realised the equivalence that these thoughts have with their own mental environment. The child can compare the second order representation with their own wider semantic environment, just as they can any pair of representations, Now the way their knowledge grows can be informed and directed via insights garnered from the thinking of others. Similarly, OP can be informed by any insights they gain as they become more aware of their own thoughts and emotions, and as they develop their understanding of the world.

This shift happens because a critical point has been reached in three regards:

- The second order representation is detailed and agile enough to allow for speedy social processing

- The child has sufficient self-knowledge and executive function to enable them to regulate, observe and direct their mental and emotional activity in a purposeful manner

- The child’s attention can now be divided – allowing them to stage their activity partner’s understanding alongside their own, and to update their own understanding based on this, in real time.

We observe the shift as a kind of revolution in the child’s self-awareness and social awareness. They are now freely picking up on our cues, intentional and unintentional. These cues point them towards useful, or adaptive understandings such as:

- How people’s thoughts, beliefs and emotions link with their actions – enriching OP

- How objects relate to one another / how they are used / what they are called – enriching the wider semantic system

As such, they find themselves learning words with astonishing ease, and sharing activities and mental states with the people around them in a much more sustained and organised manner.

In computer science terms, the mind of an 18-24 month-old gets new firmware, which enables an always-open read/write connection between the presumed thoughts of their activity partner, and their own thoughts.

When they are interacting with someone, and even when they are just observing them, the child is positing an array of presumed mental states on their behalf, ‘competing’ these against one another (based on their explanatory power), enriching all of the representations as they go, attributing the victorious representation to their activity partner, and then, most importantly, using this attributed mental state to update their own thoughts and understandings, to guide their emotional response, and to inform their actions. This process (posit-compete-enrich-attribute-compare-update) applies to the preoperational child’s understanding of thoughts and utterances.

When the preoperational child is deciding what to say to someone, they create an idealised future second order representation – the thoughts of a listener who has understood the message they wish to convey. They then stage this representation alongside their best-guess of the listener’s current mental landscape. Forms of expression suggest themselves as the child explores the semantic ground they need to cover to get from B to A (before state to after state). With this, the preoperational child is using the same basic phrase building apparatus as the adults around them.

It’s not that they are new to attributing mental states. Babies do this when you’re about to tickle them. Young toddlers do it when they notice that you’re asleep. What has changed is that they can now sustain their focus of attention onto these represented mental states, during shared experiences that have semantic content, while exercising executive control over the direction of their own thinking and their own experience.

Do lexical entries remain inside OP after the shift?

This theory positions the lexical system inside OP. Once OP finds a way to ‘talk to’ the wider semantic system, what happens to this lexicon? My assumption is that the earliest semantic formations, and the bulk of the child’s phonological and articulatory apparatus, would remain inside the OP concept. Later-acquired lexical conventions and phonological representations may be co-located with their concepts out in the wider semantic system.

This seems to account for some linguistics presentations that we see after stroke, and in dementia.

Since, in normal functioning, OP and the wider semantic system are acting as one, in all the ways we need them to, it doesn’t really matter, for the theory, where the lexicon is located.

Representing your activity partner’s mental environment – How it ‘feels’

We are driven to connect with one another via reward systems in the brain. In the course of our interactions, co-regulation feels good, and it does us good.

We are also driven chemically to grow our semantic systems, so that they will help us make our way in the world. Sudden access to powerful understandings, connections or approaches, at the first order of representation, feels good. However, sudden realisations of ignorance feel bad.

Interaction brings with it ingredients for the emotional soup from the second level of representation. If a child is going to be able to make the first cognitive shift, they will need to find a way to enjoy their soup.

Specifically then, when some aspect of our thinking is established to be original or useful (and we understand our activity partner to have updated their mental environment or actions as a result of it) this feels good. If we presume that the reward process operates on a continuum, then let’s label the thick end of the wedge ‘pride’. At the thin edge, micropride operates, registering the moments when other people’s understanding is enhanced as a result of our innovation.

Similarly, when a second order representation directs us towards a new understanding of the world, we ‘lose face’ – we should have known better. While this isn’t the case when we are being taught something or if we just don’t care, it definitely is the case when we know other people are thinking less of us because of something we know they know we got catastrophically wrong. This then is shame, at the thick end. Even if a second order representation just barely operates on a first order representation, I would expect the same type of chemical signal to be delivered, just a lot less of it. I will then call this microshame.

While these microemotions may seem to lack the dimension of personal judgement that their bigger siblings have (‘he got it wrong and I think less of him now’), it is still there, to some degree, all of the time, feeding back into the way that semantic development is being driven. These sensations would mostly be incidental during regular interaction though, unless you were highly bothered by or attuned to them. Most of the time though, conscious thoughts of shame are pushed back by:

- The soft sense of joy we feel at the first order of representation as we develop our experience, explore our world, improve our knowledge of the world, and improve our ability to function within it

- Comforting, competing social thoughts that remind us how our activity partner really feels about us.

With lots of experience weighing first and second order representations up against each other during shared activity, we can essentially start gaming the microemotion feedback system. When we’re all playing the game, we all want to be the one to achieve the more sophisticated understandings first. This shapes the way we interact and share experiences with each other, although of course this does not define how we act.

As far as these microemotions might rise to the surface, a thoughtful child, exercising executive control and directing the course of their thinking over passages of sustained socially-medicated processing, would be able to contextualise them, to respond to them and then to get right back into the micropride/microshame game, about where they left off.

I talked extensively about pride, shame, embarrassment and guilt in my first post here.

Incidentally, my understanding of Demand Avoidance is that it is, like Selective / Elective Mutism, a phobia – specifically a phobia of feeling microemotions, and it would better be treated as such. Anyway, that is not the focus today. Back to the theory.

ASD at the second order of representation

The world has moved on from Simon Baron-Cohen’s original idea that individuals with ASD entirely lack the ability to ‘mindread’, but any attempts to further characterise what it is that makes autistic brains different haven’t brought us very far, at least on my reading. If the present theory helps at all, it does so in the way it recharacterises ASD (at this level at least) as a disorder of attention control. The difficulty is not that the child with ASD cannot mindread. It’s more that they haven’t been able to make these second order representations interact productively with their own first order representations.

Specifically, at least one of the three prerequisites described above is not present:

- The second order representation is low in resolution, so the live scratchpad cannot be rendered usefully.

- The child lacks self-knowledge and executive function, making it difficult for them to regulate, observe and direct their mental and emotional activity in a purposeful manner

- The child has single-channelled attention – they can entertain their activity partner’s ideas (to some degree or other), and they can develop their own, but they cannot entertain both at the same time.

Please note – this theory makes for a highly simplified, idealised understanding of ASD. It presents a black and white view of things for the sake of simplicity. The aim here is to characterise the core autistic experience – to find something that generally holds rather than something that is true to any one person’s lived experience.

A detour to the first order of representation

The Semantic System is, simply put, a network of concepts. It is a consolidation of our world and experiences, a first order representation that works alongside our emotional battery, executive centres and limbic system to decide our actions. It’s a big part of who we are.

Until the second order representation and the wider semantic system are able to operate upon one another in a productive manner, the type and the direction of growth of the child’s semantic system will tend towards the fulfilment of their own drives and interests, and not towards the categories, relationships and distinctions that rule almost everyone else’s mental worlds.

If the child is to ‘come online’ with us, they are going to have to be open to new concepts, while updating, enriching and deeply connecting the concepts they already have. In other words, they need to keep their understanding of the world on a gentle boil somehow.

ASD at the first order of representation

Down here we need to reframe ASD as a disorder of how semantic development is driven. I propose two separate reward mechanisms, which are in balance in typical development, but one of which predominates in ASD.

The reward mechanism that predominates in ASD is the drive towards mastery. The child who spends big chunks of their day replaying the same 2 seconds of a YouTube video is doing so because this reflects the particular way that their semantic development is being driven – that is, down narrow corridors of interest.

Left to run unopposed, this drive will lead to growth of informationally encapsulated quasi-modules in the mind that relate to chosen experiences that are for the most part repetitive and predictable. Zones of interest are explored in a linear manner, as this mechanism does not reward strategies such as ‘taking two concepts together and contrasting them’.

The other mechanism rewards a child when they look at things from new perspectives, and when this yields a helpful new way of understanding those things. In other words, it is a reward for successful divergent thinking.

It adds an impulse of creativity to the way we grow our semantic system. It leads us to draw generalisations that are abstract. It encourages us to relate two concepts to one another, focusing on some properties, and brazenly ignoring others. It likes it when we make good guesses about the way things are in the world.

These new connections have the power to update or even overwrite a whole swathe of our mental environment. The higher the odds of a new connection coming through for us, the more sudden and unforeseen will be the rush of cognitive effects (in a positive context) that we feel. The higher the number of cognitive effects per unit of time, in a positive context, the better it feels.

In typical development, these two impulses counterbalance each other to inform a human character that succeeds when it is systematic, dogged, inquisitive, suspicious, convergent and divergent, all at once.

As to why autistic people might not be able to strike this balance, several reasons suggest themselves:

- They may not be able to contrast two concepts at all, social or otherwise – they cannot employ dual channelled attention.

- A rush of cognitive effects happening in a negative (or perceived negative) context (e.g., when an idea is not a good one) feels bad. The risk of negative feelings outweighs the boon of positive feelings and the child effectively disengages from this mode of discovering the world.

- The feedback they are getting through mastery simply drowns out the divergent impulse.

Similarly, when the new ideas are imported from the second order of representation, the child with ASD is either hyposensitive to the microemotions these deliver, they are hypersensitive to them, or other sensations are simply pushing these microemotions too far into the background.

All of this is pure conjecture and very abstract. Luckily it’s nowhere near the heart of the theory. Let us now head to the second big evolution in cognition that happens in early childhood, where we will find the theory has something to say.

Shift #2: The suddenly-very-canny 7/8 year old

Language processing in the preoperational stage is mechanical. The adult says words, and these words activate concepts in the child’s semantic system, domino-style. Any nuance around how specifically the adult might have intended these concepts to be activated is not available to the child. The context of understanding is something that arises alongside a given situation, rather than being something that a communicator has the power to expand, to narrow or to shift. Accordingly, interpretations at this stage are rigid, shallow and tonally neutral.

The beginning of the preoperational stage marks the moment that the child, as speaker, is able to consult their second order representation of their communication partner’s mental environment as they decide what to say (and do). As stated above, when talking, they represent a desired mental state, and they then arrange their form of expression to bring their listener to this desired point. Adults do the same thing – this never really changes.

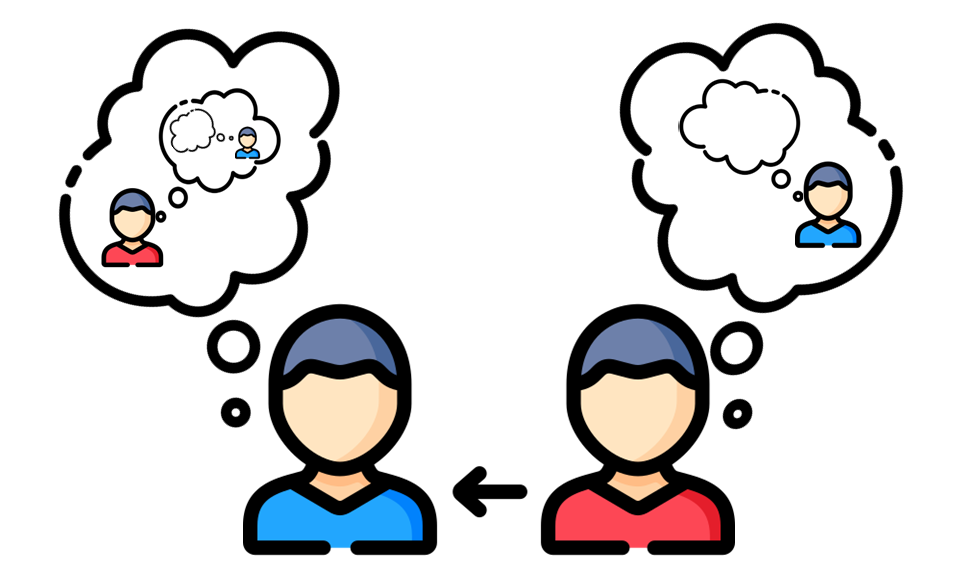

Likewise, the beginning of Piaget’s Concrete Operational Stage marks the moment that the child, as listener, is able to make a running guess at the speaker’s idea of what they (the child) should have understood from their utterance. They then use this as a reference point to guide an iterative process of utterance interpretation. They are now integrating the third order representation with their wider semantic environment.

Here’s a picture if it helps. Red is talking and Blue is listening.

Blue represents this representation and uses this to guide his interpretation of the utterance

The same mechanisms are involved as before, but now with an extra layer of attribution. Blue posits an array of presumed mental states that they can imagine Red intending. Blue ‘competes’ these against one another (based on a quick reckoning of the balance of cognitive effects that each interpretation would derive against the processing cost involved in getting there), enriching all of the representations as they go (as appropriate).

Blue attributes the victorious representation to Red. It is a third order representation – Blue’s representation of Red’s representation of Blue’s mental environment after the words (along with any extralinguistic information) have done their thing. Then, most importantly, Blue uses this double-attributed mental state to update their thoughts and understandings.

With this upgrade, the concrete-operational child is operating on the same discourse level as the adults around them.

This, for me, has the potential to be a more elegant formulation than the second communicative principle of relevance. For one thing, there’s no need to make reference to the ‘communicator’s abilities and preferences’, since both the communicator’s abilities and preferences, and their understanding of the listener’s abilities and preferences, are natural constraints that derive from the manner in which these mental environments are being metarepresented (i.e., by fallible humans) and attributed (i.e., to fallible humans).

In simple terms then, what the concrete operational child is able to do that the preoperational child is not, is to maintain their focus on the third order representation in the course of language processing. They represent the speaker’s representation of how their words should land, and then use this idealised representation to guide the way that their own semantic system responds to the words they are hearing.

This iterative process results in interpretations whose referents are fully defined and identified, and where all possible inferences are noted and tested. Anything that both parties know to exist within the shared context of interpretation can be invoked alongside the shifting representation.

In the same way as we can invoke a shift in the context, we can invoke a shift in voice. We might speak an utterance that doesn’t make sense of us, so it gets attributed to a third party, or to some conjured character. Irony is an example of this: the communicator spawns a new instance of OP, attributes an utterance or a belief to them, and invites us to think about how it must be to go about ones day in such a way.

The competence we build with these new levels of language processing can be ‘run the other way’ to help us pick our words, shape the context of interpretation, and switch voice in a highly effective manner. There is more to be said here, but as you may be able to tell, I haven’t done the thinking yet.

ASD at the third order of representation

This understanding of language processing provides an rationale for the difficulties that a child with ASD has with understanding a speaker’s full intended meaning (i.e., difficulties with drawing inferences and recognising attributional nuance). It simply states that, if the child has historically had difficulty with using the second order representation to direct the course of their thinking in a productive manner, then they’re going to find it even more challenging to make use of the third order of representation to the same end.

A philosophical aside

I have more to say, about the growth of the semantic system under the theory, about my understanding of Attachment Disorder (and Demand Avoidance) under the theory, about the rationale for certain types of therapy and possible new meta-cognitive therapies for ASD under the theory, and about the process of full utterance interpretation under the theory, but I feel I’ve gone far enough to get my basic message across for the time being.

Instead, I’ll end with an attempt to characterise what is actually happening, in the world of ideas, when two people are interacting. Here the theory looks towards Symbolic Interactionism.

When we connect together, we are effectively collaborating on a sculpture of ideas – a sculpture that neither of us will ever own or see. At the first order of representation, I have my understanding of what was said and done, and so do you. However, it doesn’t matter what individual parties understand from a conversation or an interaction. What matters is what they both agreed the other understood.

At the second order of representation, I have my understanding of your understanding of what is being said and done, and you have your understanding of my understanding of what is being said and done. The only thing that matters, in information terms, is how these two representations cohere.