As teachers, parents and therapists, we do plenty of work to help children get to grips with the basic or primary emotions, like happiness, anger and sadness, but we don’t spend as much time on the secondary emotions, such as pride, shame, guilt and embarrassment.

These emotions pack a physical punch – when we experience them, we may start to feel prickly, run hot or go clammy. We may find ourselves turning red, despite ourselves. We may even get a touch of adrenalin, which pushes our heart rate up, shifts our mental landscape, gives us the fear, and drives us towards action. They can get us in the stomach too, giving us ‘that sinking feeling’, churning us up and making us feel sick.

Children who have difficulty regulating their feelings, as well as younger children, find these physical sensations particularly jarring, upsetting and difficult to integrate. They lose their equilibrium, in all sorts of puzzling and upsetting ways, and even more mysteriously for the adults around them, they can also go to incredible lengths to avoid having to feel these feelings altogether.

These emotions are socially mediated, in that we need to be able to see ourselves through the eyes of others to experience them. Michael Lewis, director of the Institute for the Study of Child Development at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School at Rutgers, prefers the term ‘self-conscious emotions’ for them, over ‘secondary emotions’. All of our feelings are as ‘basic’ as each other, he agues. It’s just that, before around 18 months, children don’t possess the mental hardware required to register feelings like pride, shame, guilt and embarrassment. Lewis says they need to learn to be able to ‘meta-represent the self’ before they can do so.

To make sense of this, we need to define some terms around ‘representation’ . When we have a thought (e.g., ‘my sleeve is wet’; ‘the biscuit tin is empty’), we represent the world in our brains. We call these thoughts first-order representations.

During shared activity, we connect with each other by guessing each other’s thoughts (e.g., ‘he realises his sleeve is wet, he’s probably feeling uncomfortable’; ‘he wants a biscuit, he’s feeling hungry’). This process of mind-reading is supported by information from a variety of sources, such as what the person is doing, where they’re looking, their facial expressions, what we know about them, what we know about people in general (and ourselves) and so on. Representing someone else’s thoughts in this way helps us make sense of their actions and learn from them. These ‘thoughts about thoughts’ are called second-order representations.

Sometimes these represented thoughts are about us. This, then, is ‘meta-representing the self’. Some of these thoughts will be neutral in nature (e.g., ‘he is listening to something on his headphones’) and others will have some kind of value judgement included (e.g., ‘he received a high mark for his essay, he is smart’; ‘he lost us the penalty shootout, he crumbles under pressure’).

So when someone feels proud, embarrassed, guilty or shameful, they are representing someone else’s thought about them, a thought which incorporates some kind of value judgement.

A simple fellow might say that the child with autism, or the child with disordered social interaction skills, should not be able to feel these self-conscious emotions at all, because they’re not able to ‘mind-read’, or represent somebody else’s thoughts. This may be true for some children we work with, but it’s not true for many.

It’s not that children with autism are unable to entertain the thoughts of others. Most of them can, and most of these children have the self awareness to understand that that is what they are doing, to one degree or another. The difficulty they have is that they find it hard to maintain a stable connection to these represented thoughts.

Smooth interaction requires a child to establish a near-constant read/write connection to their concept of YOU, and to the little thought bubble that this concept encapsulates. They need to realise that these little thoughts are just like their own, and that they can inform their own thoughts, and vice versa. Without this stable, read/write connection, they find themselves subject to disconnected flashes of the presumed thoughts of other people.

Whereas a typically developing child might be able to ‘reason their way out’ of an embarrassing situation (‘it’s not so bad’, ‘everyone does things like this’, ‘I know they like me really’), a child with disordered social interaction skills will likely bounce away from these thoughts, and their associated physical responses, without rationalising them in any way.

Cringe: Meta-embarrassment

I promised there would be cringe. Among the ‘self-conscious emotions’, cringe is particularly poorly understood. Susie Dent, in her excellent Emotional Dictionary doesn’t have much to say about it beyond its etymology (it’s a relative of ‘cranky’, with both words carrying the idea of being bent out of shape, or doubled over). The OED has it as ‘an inward feeling of acute awkwardness or embarrassment’, which doesn’t add a lot to proceedings either. Widgit Online doesn’t even have a symbol for cringe, and it’s not mentioned in emotional curricula such as Talkabout, Socially Speaking, or the Zones of Regulation.

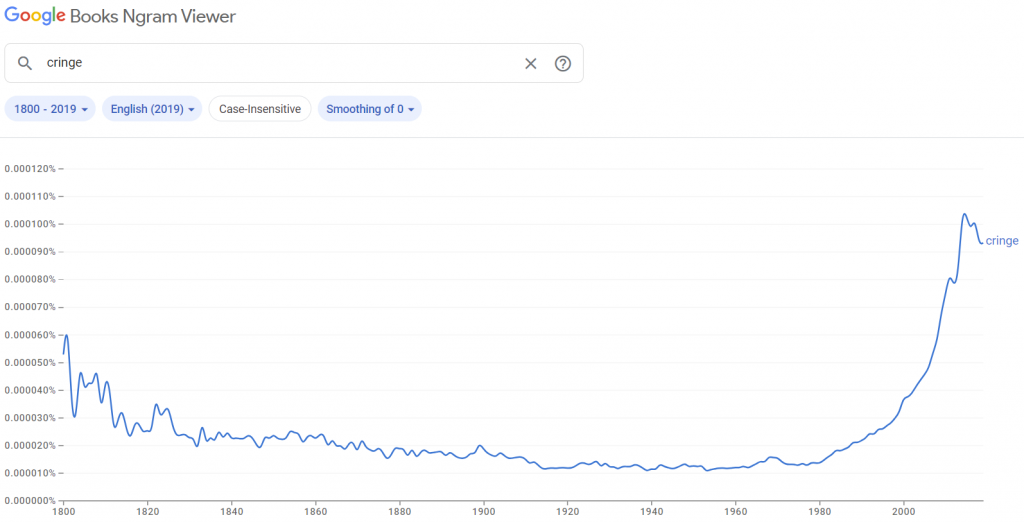

While we might not be very good at explaining it, there sure is a lot of it about. Indeed, a frequency analysis of the word suggests that we are in the midst of something of a cringe pandemic.

Cringe is a very 21st century feeling then, but what actually is it? A step towards understanding it might be to try to differentiate it from its relatives: embarrassment, shame and guilt.

Embarrassment is an immediate response to a situation where the image of yourself that you seek to project to others has been undermined. You did something, it wasn’t great, someone noticed, and now you feel embarrassed. You are representing the thoughts of that person, and those thoughts are judging you.

Shame is similar, but with shame there is something of a moral dimension folded in. You don’t just sense that you are being judged a fool. With shame, it is your entire character and good name that is at question. Again, you are representing thoughts that others are having about you.

Guilt is spicier still, because you’ve done something embarrassing or shameful around somebody who hasn’t noticed (or maybe acknowledged) whatever it was you did, leaving you ruminating over thoughts such as ‘what will they think of me if they find out’ and ‘can I live with this secret’. You are representing thoughts other people might have about you at some point in the future.

How does cringe relate to these ‘second-order’ emotions then? The answer is that it exists on a higher plane entirely – it is a ‘third-order’ emotion, where the thoughts of others that we represent are themselves second-order representations of the judgemental thoughts that they perceive others to be having about them.

As far as I can work out, we use the word ‘cringe’ to describe a range of related emotions and feelings, and all of them require third-order representations. They include:

- Personal cringe, where you replay the actions of your former self, press pause, and then submit yourself to a reflective pang of embarrassment. It’s meta-embarrassment. You don’t feel embarrassed per se, but past you certainly does, and you are representing past you’s representation of what other people were thinking about you.

- Second-hand cringe, where you are subject to someone else’s embarrassment. Second-hand cringe is meta-embarrassment, as you are representing someone’s thoughts about someone else’s thoughts concerning them.

* If you feel a deep affinity to that individual, there will be significant personal embarrassment as part of the emotional cocktail you experience.

* There may be an inadvertent transference of embarrassment, where the cringy person is too oblivious to feel the embarrassment that we would (and basically do) feel in their place. This is the true ‘I’m embarrassed for you’ feeling.

* There may also be a forced transference of embarrassment, where someone acts shamelessly, daring you to engage your moral compass and showing you just how little your opinions mean to them. - Another ‘forced’ variant I would call 4D cringe, where you find yourself trapped on a cringe island of somebody else’s design, e.g., when you are watching a performance of some kind.

It’s this final, unfolding type of cringe that interests me the most. This is the source of the existential terror I felt during a live performance of the Sooty Show that I went to at the age of about 6. It’s the reason my niece cried when we took her to The Galleries of Justice here in Nottingham, and she had to watch someone acting out a famous historical trial.

We don’t just feel it during face to face experiences either. I feel it when I’m watching The Inbetweeners. In fact, I don’t, because the sense of cringe is so great with that programme, that I can’t bring myself to watch it, being totally unable to face the grindingly predictable and utterly mortifying outcomes that come into focus for the characters during the final act. I feel it as I switch the channel to avoid having to watch a pitch go south on Dragon’s Den. I feel it as I hide behind a pillow as the candidates on The Apprentice host their appallingly ill-conceived events. It’s not that I don’t want to watch these things. I just can’t.

Escape from Cringe Island

The thing is, I think we are subjecting our children to this feeling throughout their days. While we are innocently trying to engage them, we are actually trapping them on cringe island, forcing them to think about how embarrassed we are (or how embarrassed we should be).

It’s not even necessarily embarrassment that they need to be detecting – it’s any second order thought of ours that they find themselves representing (e.g., ‘I want you to enjoy this’).

To be specific – I’m often warned by teaching assistants ‘don’t sing to him, he doesn’t like it and it makes him kick off’. I usually sing to these children anyway, because I’m a deeply wilful individual. In my experience, it’s not that they don’t like music, or singing, or even being sung to. What they can’t cope with is the 4D cringe that the situation subjects them to. They’ve heard this song before. They’ve thought all these thoughts before. They know what I’m doing to do next, they know what I’m thinking, and I should be ashamed.

They also know all of the social expectations that accompany the song – certainly some kind of social response will be expected of them. Even if they give us nothing, they can’t help but enter into a sustained form of social processing, as the song unfolds before them. This kind of performance places strong demands on children with disordered social skills, and it offers them no way out.

Why do I put them through this then, by insisting on singing to them? The answer is, I don’t, because I am aware of how they are feeling, so instead of serving them straight cringe, I subvert their expectations. It’s only cringe if they know, within some sort of bounds, what is going to happen, so I lean into the situation a little. I sing too low, too high or all warbly. I get the words wrong. I make everything surprising and weird enough to give them a reason to process what I am doing, to think afresh. This approach works for me anyway – I find it keeps these child socially engaged for longer.

At least I have a rationale for being weird. What’s everyone else’s excuse?

[There is another emotion that makes use of third-order representations – shadenfreude, where we feel a sense of relief, or even satisfaction, as we observe someone else experiencing embarrassment. Cringe and shadenfreude are siblings].